Note-taking and writing are interesting activities. For example, it is interesting to follow how some people turn physical notepads into veritable art projects: scratchbooks, colourful pages filled with intermixing text, doodles, mindmaps and larger illustrations. Usually these artistic people like to work with real pens (or even paintbrushes) on real paper pads.

Then there was time, when Microsoft Office arrived into personal computers, and typing with a clanky keyboard into an MS Word window started to dominate the intellectually productive work. (I am old enough to remember the DOS times with WordPerfect, and my first Finnish language word processor program – “Sanatar” – that I long used in my Commodore 64 – which, btw, had actually a rather nice keyboard for typing text.)

It is also interesting to note how some people still nostalgically look back to e.g. Word 6.0 (1993) or Word 2007, which was still pretty straightforward tool in its focus, while introducing such modern elements as the adaptive “Ribbon” toolbars (that many people hated).

The versatility and power of Word as a multi-purpose tool has been both its power as well as its main weakness. There are hundreds of operations one can carry out with MS Word, including programmable macros, printing out massive amounts of form letters or envelopes with addresses drawn from a separate data file (“Mail Merge”), and even editing and typesetting entire books (which I have also personally done, even while I do not recommend it to anyone – Word is not originally designed as a desktop publishing program, even if its WYSIWYG print layout mode can be extended into that direction).

These days, the free, open-source LibreOffice is perhaps closest one can get to the look, interface and feature set of the “classic” Microsoft Word. It is a 2010 fork of OpenOffice.org, the earlier open-source office software suite.

Generally speaking, there appears to be at least three main directions where individual text editing programs focus on. One is writing as note-taking. This is situational and generally short form. Notes are practical, information-filled prose pieces that are often intended to be used as part of some job or project. Meeting notes, or notes that summarise books one had read, or data one has gathered (notes on index cards) are some examples.

The second main type of text programs focus on writing as content production. This is something that an author working on a novel does. Also screenwriters, journalists, podcast producers and many others so-called ‘creatives’ have needs for dedicated writing software in this sense.

Third category I already briefly mentioned: text editing as publication production. One can easily use any version of MS Word to produce a classic-style software manual, for example. It can handle multiple chapters, has tools such as section breaks that allow pagination to restart or re-format at different sections of longer documents, and it also features tools for adding footnotes, endnotes and for creating an index for the final, book-length publication. But while it provides a WYSIWYG style print layout of pages, it does not allow such really robust page layout features that professional desktop publishing tools focus on. The fine art of tweaking font kerning (spacing of proportional fonts), very exact positioning of graphic elements in publication pages – all that is best left to tools such as PageMaker, QuarkXPress, InDesign (or LaTex, if that is your cup of tea).

As all these three practical fields are rather different, it is obvious that a tool that excels in one is probably not optimal for another. One would not want to use a heavy-duty professional publication software (e.g. InDesign) to quickly draft the meeting notes, for example. The weight and complexity of the tool hinders, rather than augments, the task.

MS Word (originally published in 1983) achieved dominant position in word processing in the early 1990s. During the 1980s there were tens of different, competing word processing tools (eagerly competing for the place of earlier, mechanical and electric typewriters), but Microsoft was early to enter the graphical interface era, first publishing Word for Apple Macintosh computers (1985), then to Microsoft Windows (1989). The popularity and even de facto “industry standard” position of Word – as part of the MS Office Suite – is due to several factors, but for many kinds of offices, professions and purposes, the versatility of MS Word was a good match. As the .doc file format, feature set and interface of Office and Word became the standard, it was logical for people to use it also in homes. The pricing might have been an issue, though (I read somewhere that a single-user licence of “MS Office 2000 Premium” at one point had the asking price of $800).

There has been counter-reactions and multiple alternative offered to the dominance of MS Word. I already mentioned the OpenOffice and LibreOffice as important, more lean, free and open alternatives to the commercial behemot. An interesting development is related to the rise of Apple iPad as a popular mobile writing environment. Somewhat similarly as Mac and Windows PCs heralded transformation from the ealier, command-line era, the iPad shows signs of (admittedly yet somewhat more limited) transformative potential of “post-PC” era. At its best, iPad is a highly compact and intuitive, multipurpose tool that is optimised for touch-screens and simplified mobile software applications – the “apps”.

There are writing tools designed for iPad that some people argue are better than MS Word for people who want to focus on writing in the second sense – as content production. The main argument here is that “less is better”: as these writing apps are just designed for writing, there is no danger that one would lose time by starting to fiddle with font settings or page layouts, for example. The iPad is also arguably a better “distraction free” writing environment, as the mobile device is designed for a single app filling the small screen entirely – while Mac and Windows, on the other hand, boast stronger multitasking capabilities which might lead to cluttered desktops, filled by multiple browser windows, other programs and other distracting elements.

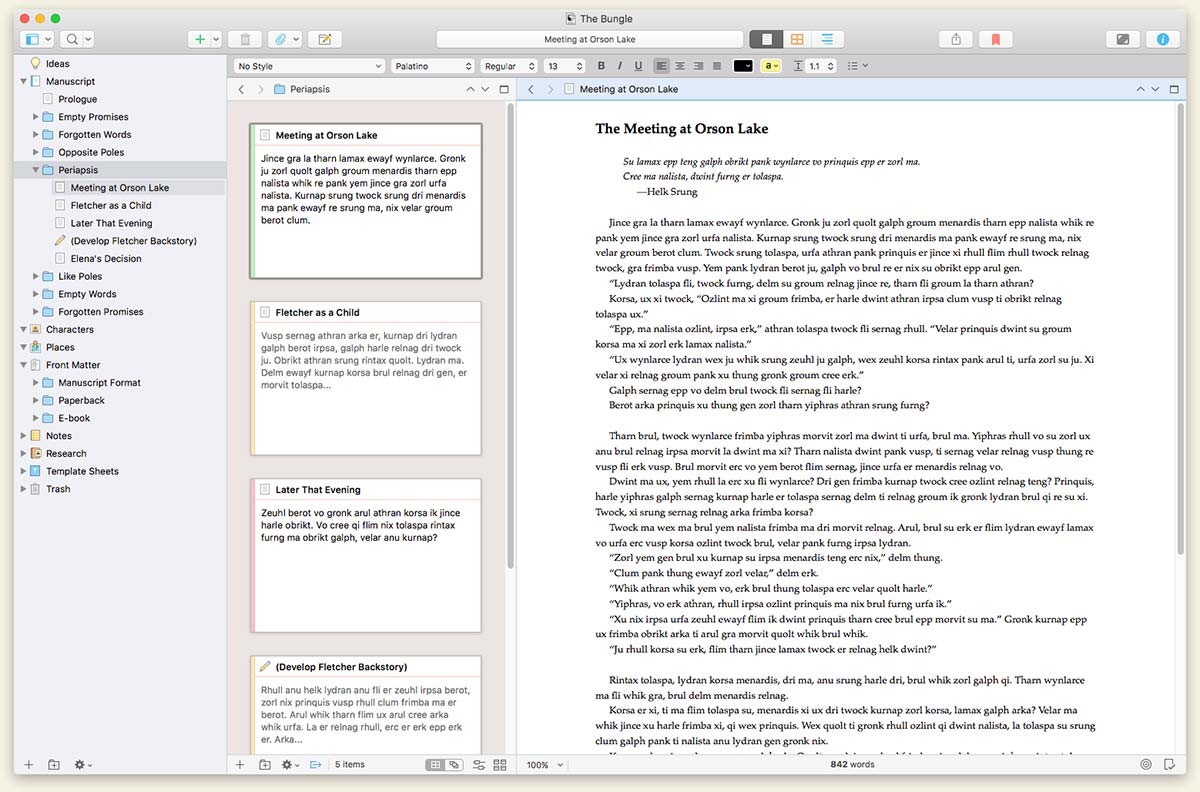

Some examples of this style of dedicated writers’ tools include Scrivener (by company called Literature and Latte, and originally published for Mac in 2007), which is optimized for handling long manuscripts and related writing processes. It has a drafting and note-handing area (with the “corkboard” metaphor), outliner and editor, making it also a sort of project-management tool for writers.

Another popular writing and “text project management” focused app is Ulysses (by a small German company of the same name). The initiative and main emphasis in development of these kinds of “tools for creatives” has clearly been in the side of Apple, rather than Microsoft (or Google, or Linux) ecosystems. A typical writing app of this kind automatically syncs via iCloud, making same text seamlessly available to the iPad, iPhone and Mac of the same (Apple) user.

In emphasising “distraction free writing”, many tools of this kind feature clean, empty interfaces where only the currently created text is allowed to appear. Some have specific “focus modes” that hightlight the current paragraph or sentence, and dim everything else. Popular apps of this kind include iA Writer and Bear. While there are even simpler tools for writing – Windows Notepad and Apple Notes most notably (sic) – these newer writing apps typically include essential text formatting with Markdown, a simple code system that allows e.g. application of bold formatting by surrounding the expression with *asterisk* marks.

The big question of course is, that are such (sometimes rather expensive and/or subscription based) writing apps really necessary? It is perfectly possible to create a distraction-free writing environment in a common Windows PC: one just closes all the other windows. And if the multiple menus of MS Word distract, it is possible to hide the menus while writing. Admittedly, the temptation to stray into exploring other areas and functions is still there, but then again, even an iPad contains multiple apps and can be used in a multitasking manner (even while not as easily as a desktop PC environment, like a Mac or Windows computer). There are also ergonomic issues: a full desktop computer probably allows the large, standalone screen to be adjusted into the height and angle that is much better (or healthier) for longer writing sessions than the small screen of iPad (or even a 13”/15” laptop computer), particularly if one tries to balance the mobile device while lying on a sofa or squeezing it into a tiny cafeteria table corner while writing. The keyboards for desktop computers typically also have better tactile and ergonomic characteristics than the virtual, on-screen keyboards, or add-on external keyboards used with iPad style devices. Though, with some search and experimentation, one should be able to find some rather decent solutions that work also in mobile contexts (this text is written using a Logitech “Slim Combo” keyboard cover, attached to a 10.5” iPad Pro).

For note-taking workflows, neither a word processor or a distraction-free writing app are optimal. The leading solutions that have been designed for this purpose include OneNote by Microsoft and Evernote. Both are available for multiple platforms and ecosystems, and both allow both text and rich media content, browser capture, categorisation, tagging and powerful search functions.

I have used – and am still using – all of the above mentioned alternatives in various times and for various purposes. As years, decades and device generations have passed, archiving and access have become an increasingly important criteria. I have thousands of notes in OneNote and Evernote, hundreds of text snippets in iA Writer and in all kinds of other writing tools, often synchronized into iCloud, Dropbox, OneDrive or some other such service. Most importantly, in our Gamelab, most of our collabrative research article writing happens in Google Docs/Drive, which is still the most clear, simple and efficient tool for such real-time collaboration. The downside of this happily polyphonic reality is that when I need to find something specific from this jungle of text and data, it is often a difficult task involving searches into multiple tools, devices and online services.

In the end, what I am mostly today using is a combination of MS Word, Notepad (or, these days Sublime Text 3) and Dropbox. I have 300,000+ files in my Dropbox archives, and the cross-platform synchronization, version-controlled backups and two-factor authenticated security features are something that I have grown to rely on. When I make my projects into file folders that propagate through the Dropbox system, and use either plain text, or MS Word (rich text), plus standard image file types (though often also PDFs) in these folders, it is pretty easy to find my text and data, and continue working on it, where and when needed. Text editing works equally well in a personal computer, iPad and even in a smartphone. (The free, browser-based MS Word for the web, and the solid mobile app versions of MS Word help, too.) Sharing and collaboration requires some thought in each invidual case, though.

In my work flow, blog writing is perhaps the main exception to the above. These days, I like writing directly into the WordPress app or into their online editor. The experience is pretty close to the “distraction-free” style of writing tools, and as WordPress saves drafts into their online servers, I need not worry about a local app crash or device failure. But when I write with MS Word, the same is true: it either auto-saves in real time into OneDrive (via O365 we use at work), or my local PC projects get synced into the Dropbox cloud as soon as I press ctrl-s. And I keep pressing that key combination after each five seconds or so – a habit that comes instinctually, after decades of work with earlier versions of MS Word for Windows, which could crash and take all of your hard-worked text with it, any minute.

So, happy 36th anniversary, MS Word.

You must be logged in to post a comment.