No-one asked for this, but I will provide some bird/wildlife photography gear suggestions below, anyways. This is only focused on the Canon options, because that is where I have my personal experience. (Canon is the leading camera manufacturer, but many other probably have somewhat similar options.) The use-case and price are major factors, so I have estimated those (quoted prices are something that I could find currently here in Finland). Any comments are welcome! 😊

Beginner / occasional nature photographer’s suggested option:

- Canon EOS R50 / M50 Mark II & Sigma 150-600mm f/5-6,3 DG OS HSM Contemporary

- Price: 1748 euros = 669 euros (M50m2) + 1079 euros (Sigma150-600) (Note: the new R50 will be priced here at c. 879 euros)

- Pros: over 24 megapixels, APS-C (with 1.6x crop) brings wildlife closer; Dual Pixel autofocus is generally good and pretty fast. Simple and easy to use.

- Cons: these entry-level cameras are pretty small, ergonomics is not good, there is no wheel or joystick control, one must use the touch screen to move fast the AF area while taking photos; the Sigma lens provides good reach (225-960mm in full-frame terms), but it needs an EF-adapter, and it is slower and more uncertain to focus than a true, modern Canon RF-mount lens. And frankly, these cameras are optimized for taking photos of people rather than birds or wildlife, but they can be stretched for it, too. (This is where I started when I moved from more general photography to bird-focused nature photography, three years ago.)

Travelling, and weekend nature photographer’s suggested option:

- Canon EOS R7 & RF 100-400mm f/5.6-8 IS USM

- Price: 2448 euros = 1699 euros (R7) + 749 euros (RF100-400)

- Pros: R7 is a very lightweight, yet capable camera – it has 33-megapixel APS-C sensor, the new Digic X processor, a blazingly fast 30 fps electronic shutter, two SDXC UHS-II card slots, IBIS (image stabilization), Dual Pixel AF II with animal eye-focus, and even some weather sealing.

- Cons: the 651 AF focus points is good, but not pro-level; the camera will every now and then fail to lock focus. The sensor read speed is slow, leading to noticeable “rolling shutter” distortion effects, relating to camera movement during shooting. One needs to shoot more frames, to get some that are distortion-free. There is also only one control wheel, set in “non-standard” position around the joystick. RF100-400 lens is a really nice “walkaround lens” for R7 (it is 160-640mm in full-frame terms). But if the reach is the key priority rather than mobility, then one could consider a heavier option, like the Sigma 150-600mm above.

Enthusiast / advanced hobbyist option:

- Canon EOS R5 & RF 100-500mm f/4.5-7.1 L IS USM

- Price: 6939 euros = 3700 euros (R5, a campaign price right now) + 3239 euros (RF100-500)

- Pros: R5 is already a more pro-level tool; it is weather sealed, has a 45-megapixel sensor, Digic X, 20 fps, IBIS, animal eye-focus with 5940 focus points, dual slots (CFexpress Type B, & SD/SDHC/SDXC), etc.

- Cons: this combination is much heavier to carry around than the above, R7 one (738+1365g vs. 612+635g). There will probably be a “Mark II” of R5 coming within a year or so (the AF system and some features are already “old generation” as compared to R3 / R7). The combination of full-frame sensor and max 500mm focal length means that far-away targets will be rather small in the viewfinder; the 45-megapixel sensor will provide considerable room for cropping in editing, though.

Working professional / bathing-in-money option:

- Canon EOS R3 & RF 600mm F4 L IS USM

- Price: 19990 euros = 5990 euros (R3) + 14000 euros (RF600)

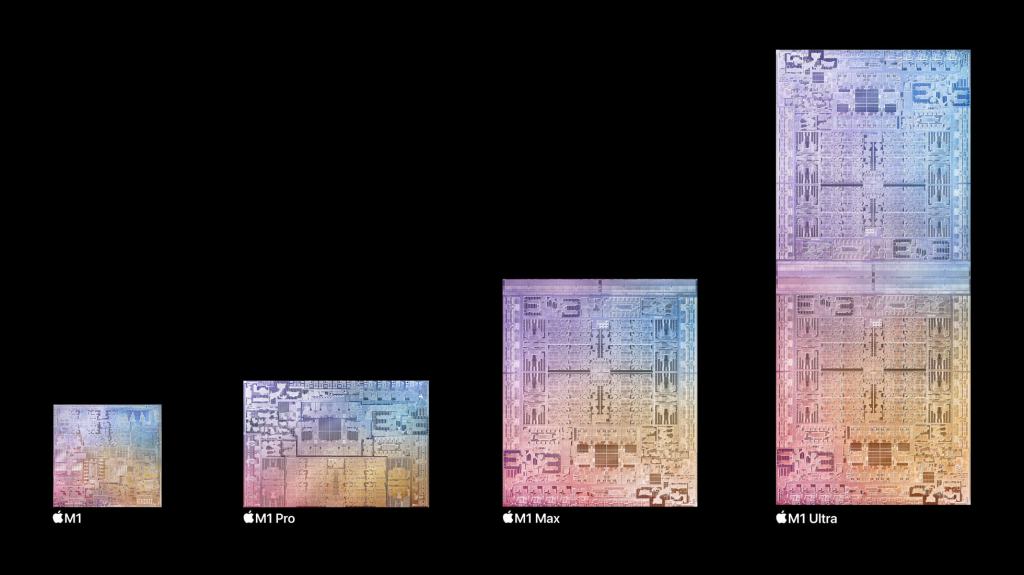

- Pros: new generation back-illuminated, stacked sensor (24 megapixels), max 30 fps, max ISO 204800, Digic X, new generation eye-controlled AF, enhanced subject tracking, 4779 selectable AF points, etc.

- Cons: R3 is the current “flagship” of Canon mirrorless systems, but in terms of pixel count, it is behind R5. Some professionals prefer the speed and more advanced autofocus system of R3, while some use R5 because it allows more sharp pixels / room for cropping in the editing phase. The key element here is the (monstrously sized) professional 600mm f/4 prime lens. The image quality and subject separation is beyond anything that the more reasonably priced lenses can offer. The downside is that these kinds of lenses are huge, require mounting them on a tripod pretty much always when you shoot, and the price, of course, puts these out of question for most amateur nature photographers. (Note: as a colleague commented, these large lenses can also be found used sometimes, for much cheaper, if one is lucky.)

And there are, of course, ways of mixing and combining cameras and lenses in many other ways, too, but these are what I consider notable options that differ clearly in terms of use-case (and pricing).

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3423214/7024888627_3257c520fd_k.0.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.